I was being swallowed up by a place that was supposed to be familiar. I watched as dilapidated buildings slid over my windshield like crooked teeth in a mouth full of hate. Shotgun houses—with siding that curled and porch awnings that pitched and slanted like the grins of idiots—watched me make my way down the lane in my little rental car. Ditches that I’d always thought of as too deep for such a narrow street flanked me on either side.

Memories of swimming and splashing in them with the other poor kids bubbled up from the deeper parts of my mind. Summer rains would flood the storm drains with water like chocolate milk and we’d try not to get sucked into the culverts. We’d emerge from the muddy water, into the overcast heat, peppered with leeches whose anesthetic mouths kept us clueless while they planted razored kisses all over our sunburned bodies.

For better or worse, this street was home. At least, it had been. Over the years, I’d managed to run far from it in just about every way that could matter. I’d kept off the drugs—the hard ones that bloom sores across sunken cheeks and lead to shrunken teeth like the withered smiles of jack-o-lanterns left too long in a Kentucky sun. I’d managed to stay out of jail and prison—an anomaly in my family and neighborhood. I had even, through joining the military, escaped the type of crushing poverty that sits heavily on people’s chests, making it hard to breathe. I’d felt that feeling before, but never quite understood it. The air was free, after all. It was having a dream that would cost you.

I got the call by way of a text message, the one we’re all destined to get, provided we live long enough to answer the phone: Last chance to say goodbye. She’s going down fast. I didn’t want to say goodbye, though. I didn’t want to come back to this place, return to a world that I’d managed to claw myself out of—not because I was ashamed. The time for shame over such things had long since passed in my life. It’s just that, to me, it’s always been better to look forward rather than to dwell on the past—to focus on what could still yet be instead of stirring up all the things that have already gone by.

DOUBLE-WIDE DREAMS:

The first time I heard the phrase white flight was during a gen-ed course on American History. The kind but dusty old professor tossed the word out there in passing like we were all supposed to know what it meant. Then he clicked to the next slide, and he rambled on. I’d only recently begun attending college, after a decade spent in the U.S. Navy, and I sat surrounded by mostly twenty-somethings who nodded along in understanding. I didn’t understand the phrase, though. In fact, I’m confident I had never heard it up until that point. So, I raised my hand and asked the professor what it meant.

He explained to me that, in the aftermath of the Second World War, white families fled the cities to get away from black and brown folks. Then, he clicked for the next slide and rumbled along like an old locomotive cutting a familiar track. Meanwhile, I was thrown into the past, my imagination grinding its gears until I was back in the only place I recall my family ever managing to escape.

It was a single-wide in a run-down trailer park, choked with overgrown weeds and crisscrossed by underwhelming gravel thoroughfares. I remember feeling relief when we said goodbye to that tin-walled tumbleweed, mainly at the prospect of no longer having to flee it each time a tornado siren would scream down the county road. Aside from that feeling, I have only two other memories of that haggard place: when the manager of the mobile home park gave me a concussion, and that time I burned my rear end getting out of a cold bath.

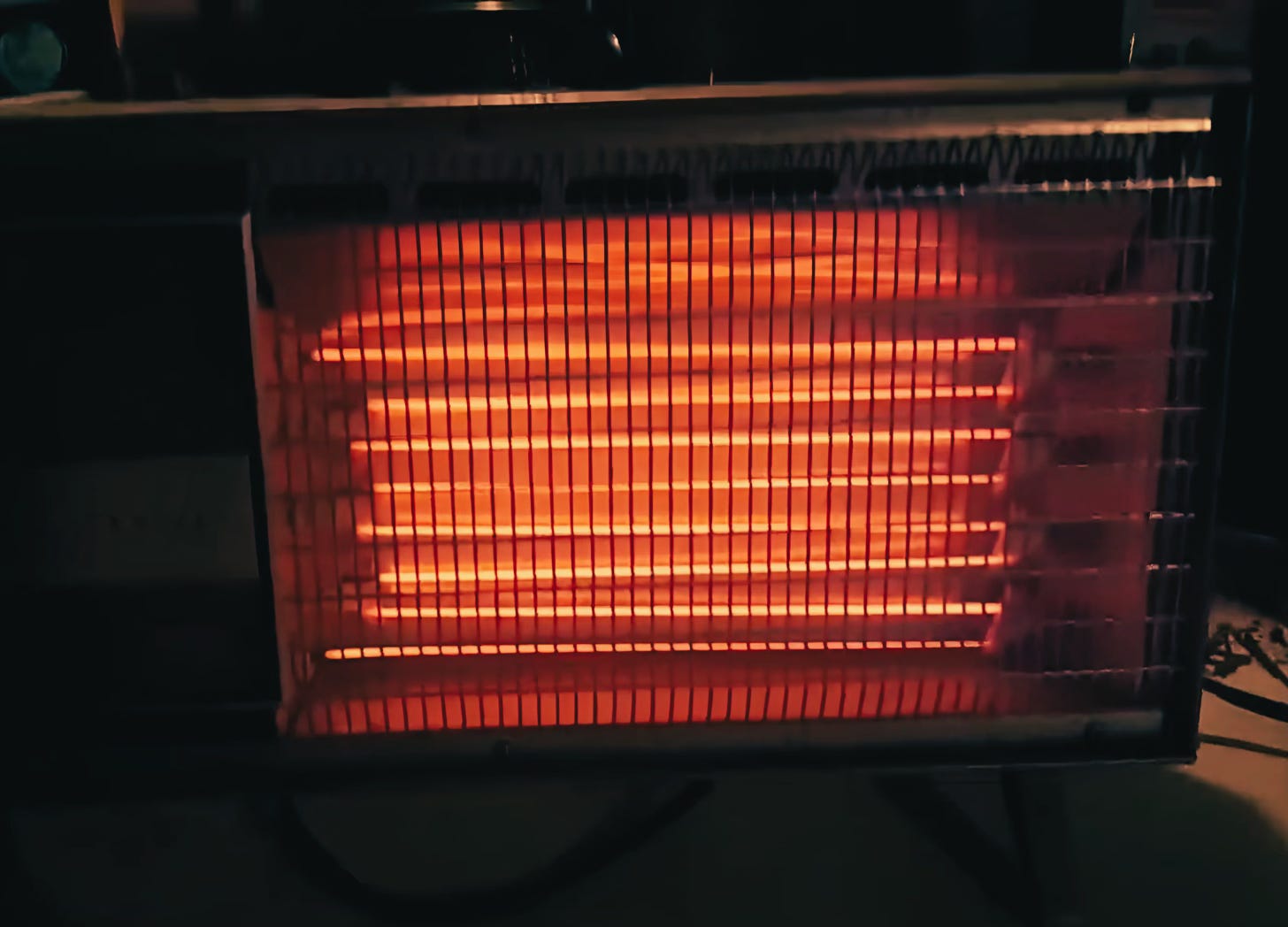

You can be forgiven for not knowing that mobile homes aren’t renowned for their heat retention properties. In the wintertime, in ours, you could damn near see your breath. There was no central heat, and we didn’t have the funds for such luxuries as everyone having their own individual warm bath. On a day when it was my turn to go last, the water was already frigid by the time I got undressed. My mother brought in an ancient box heater and set it as close to the bathtub as the electrical-taped cord could manage. The thing buzzed like a crate of resentful bees from an angry distance that was both too far to be effective and too close to be safe.

I moved like white lightning—in and out of the tub in a blur—sudsing just the important parts of my skinny body before momentarily dunking beneath the chilly water. When I stepped out of the bath, only partially rinsed and chattering, I wrapped myself in a ratty towel and huddled in front of the little heater to warm back up. I inched closer to its orangey glow, jagged electrical wires putting off pitiful heat. The thing was doing its disgruntled best but still could only manage to warm small patches of my body at any given moment. So, I inched closer, rotating like a vertical, voluntary rotisserie chicken. Closer. When my rear end pressed and sizzled against the metal grill that caged the front of the heater, I yelped, and my hands teleported to my backside. As my pale ass flew entirely too close to the electrical sun, I shot into the air in the only version of white flight that I would ever know.

I don’t remember exactly how old I was when we finally moved out of that place, but I do remember it feeling like a dream. Nor do I remember how many months passed between the first time I heard the term white flight and the first time a professor used the words white privilege. That felt like a dream, too, though not the good kind. I remember feeling personally attacked— watching all the struggle and effort and sacrifice it took for me to climb out of the squalor and chaos that I had been born into disappear like warm air through the drafty eaves of an old single-wide trailer. Then I remember being very, very angry. These days, it seems like a lot of other people are, too. Maybe that’s a good thing.

DOWNSTREAM FAREWELL:

I got the call by way of a text message, and I hesitated. Knowing what was fact and fiction with her had always been hard, especially toward the end. When I was growing up, I never knew if the stories she told about my childhood were real or not, and that had made things difficult then. Now, however, I think I can see what she was up to. Sometimes, when reality is too hard and too flat, a fiction can be a balm of sorts, or—as I discovered in the pages of novels that took me far away—it can serve as an escape route. It can add a little color to drab pages of black and white. It can change the story. At least for a time.

After my older brother texted me, I called the nurse station, and a man who sounded like Foghorn Leghorn answered from two thousand miles away. He laughed and told me that she was doing just fine, that she had been up and walking, and that he had been in her room yuckin’ it up with her all morning—said, “Boy, ain’t she somethin'.” I was inclined to agree.

I hung up, relief filling my lungs like welcome air, and I decided to wait. The next day, my brother texted me again, more urgent this time, and I dialed the nurse station once more. Foghorn-Leghorn answered, but there was no bounce in his words today—no pep in his verbal giddyup. He said it was bad—real bad—"say sorry”. I hung up the phone and bought a one-way ticket, knowing in my heart that I would never make it on time. I’m ashamed to admit that a terrible, miserable part of me was relieved. So, I had to make do with saying goodbye at a river.

Much of the childhood that I’d forgotten, that I’d distanced myself from, caught up to me like some long-lost shadow that I’d shaken loose somewhere along the way. As I drove down my narrow street with its too-deep ditches toward my childhood home, I was hit with a realization that I’d likely always known, at least on some level. It takes a real son-of-a-bitch to convince kids—boys and girls who are, at this moment, growing up in ways similar to my own, and worse—that they’re somehow privileged by dint of the color of their skin.

You have to have a dark heart to snuff out the already weak fires that burn within their sometimes-empty bellies, fires that will need to roar like an angry river for them to even stand a snowball’s chance of making it out of the circumstances they were born into. What type of person would also demand that they add blood debt and back-of-the-line obligation to their non-existent inheritance? My mother died with three hundred dollars to her name, a stack of past-due bills, and a desktop littered with high-interest loan denials. Was she privileged, too?

I said goodbye to my mother at the river, while the muddy waters of the Ohio did their lazy best to slow the flat-bottomed freight trains of floating cargo pushed along by the sleepy barges, because I arrived too late to do it in person. I’m not sure she would have wanted me there, if I’m being honest. Such was our relationship by the time she passed. I stared into that water, and a part of me couldn’t help but see bigger versions of us kids playing and splashing in those chocolate-colored currents. Then I closed my eyes.

The most beautiful thing about a river is that it continues on, and that change is always just around the next bend. Oftentimes, I count it a kindness that some old dead philosopher was correct when he said that no man can enter the same river twice. I said goodbye to her at the river. If there was one privilege I had in this life based upon my skin, it had nothing to do with the color that it was and everything to do with the woman who made it for me.